Patriotic Education was introduced in China in 1989 in the wake of the Democracy Movement that met its end in the Tiananmen Square massacre. Since then, children all over China have grown up with the concept of guochi (‘National Humiliation’) drilled into them in the history classroom. The narrative the Chinese government wish to install in this way is that China was humbled by foreign powers during most of the 19th century because it was weak, now the Communist Party has taken over, made the country strong, and put a stop to this, and rightfully deserves the peoples’ support.

The list of foreign interference in the form of unfair treaties, military confrontations and ruined historic buildings e.g. the destruction of the Summer Palace in China during this time of imperial encroachment is almost limitless. Unfortunately, Europe, and particularly Britain, took a leading role in the exploitation of China’s trade possibilities. The Ching dynasty and those in charge all over China were fairly hostile to the new technologies that westerners offered, all too eagerly, to bring over with them. Many Europeans, however, saw the huge untapped opportunities in the country for rail transport. The only obstacle was overcoming the natural Chinese opposition to what they considered ‘flame breathing machines’ and the laying of railroads, which according to most Chinese villagers would disturb the feng shui of the areas it ran through.

Understandably, at the time as well as now, there was and is resentment from many Chinese people for the way the imperial powers subjugated their people and treated their land. This was the environment in which six men from Ipswich set out to attempt the unlikely and unwanted task of building the first railroad in China. On top of all the other hardships they would have to face in the process, it’s worth remembering that they probably weren’t too welcome there either.

(Above) The ruins of the Summer Palace destroyed in the Arrow War – one of many important sites that the Chinese government point towards to support the concept of guochi.

Richard Rapier, of the company Ransomes and Rapier based in Ipswich, was a man with a plan; he wanted to be the person responsible for the first railroad in China. He understood the very real gains on offer if China was truly opened up to Western travel and commerce through the development of a Chinese rail network.

Rapier took his first real shot at the project in 1872, by arguing that a miniature railway could be sent as a gift from the British to the emperor, seventeen year old Tung Chih. Rapier’s idea was to sweeten the new emperor up with his very own ‘toy’ train, so as to inspire the Chinese Imperial Court to permit or even encourage the development of full sized railways in the face of the opposition being experienced. Unfortunately for Rapier’s proposal, the Chinese were seen to have something of a superiority complex at the time and it was feared that any gift of such a size would be seen as a form of tribute, which could undo much of the work done by the British to counter the Chinese perception of superiority. This spelled the temporary end to Rapiers ambition. It was also unfortunate for Tung Chih, who, without the distraction of a toy railway, turned to the next best form of entertainment – Peking’s brothels – resulting in his death just two years later, at the age of nineteen, from a combination of syphilis and smallpox.

Despite this set back, Rapier continued to work on the development of a lightweight locomotive and railway that could be shipped to China, and in 1875 a real chance finally came for him to realise his dream.

The Woosung Road Company requested a meeting with Rapier to discuss supplying a small railway for Shanghai. Upon the companies visit to Rapier in Ipswich, he so impressed them with his little engine ‘pioneer’ they decided they had found the right man and at once engaged him to provide the entire railway system they had in mind.

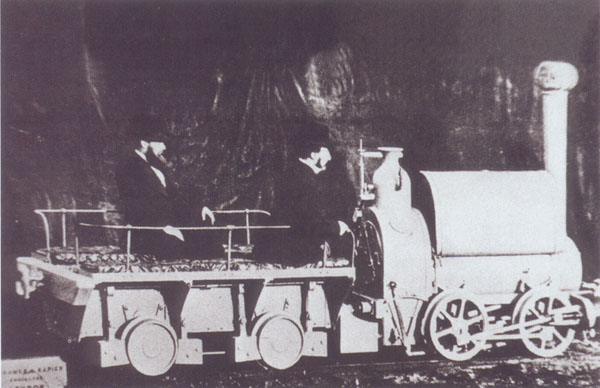

Pioneer – China’s first railway engine.

Pioneer – China’s first railway engine.

With a deal agreed, Rapier set about manufacturing and assembling China’s first railway in his Waterside Works in Ipswich. All this took place without the permission or slightest knowledge of the Chinese government.

On the 1st October 1876 the engine, railway and six Englishmen left England for shanghai via America in the SS Glenroy. The six men from Ipswich were: Gabriel James Morrison M.Inst. C.E and his assistants John Sadler as chief foreman, William George Jackson and David Edward Banks as engine drivers, John Sadler Jnr. as second foreman and George Sadler as general assistant.

Upon their arrival in China these men, with the help of Chinese labourers, worked to lay the first railroad in China’s history along with bridges, turntables and stations from Shanhai to Woosung. This was no easy task as they had to deal with an extreme climate and long hours of arduous work, which caused them severe health problems. By September 1876 the project had cost the senior John Sadler his life with only half the line being laid. Then George Sadler became ill and had to be sent home under the care of his brother John. This left the project very short staffed, but even faced with these difficulties the team still managed to get the line open and running a passenger service by 1877.

China’s first railway ran from Shanghai to Woosung (now part of an enlarged Shanghai)

China’s first railway ran from Shanghai to Woosung (now part of an enlarged Shanghai)

Pioneer, the first train to be used on Chinese tracks, was set on a 30” gauge to fit the new line being built, it was capable of running up to 20mph and was able to haul up to 20 tons. Two further Ipswich built engines were transferred to Shanghai to be used for the new passenger service named Celestial Empire and Flowery Land, these were improvements on the Pioneer design and were able to haul more weight and travel at faster speeds.

Celestial Empire pulling the Shanghai to Woosung passenger service

Celestial Empire pulling the Shanghai to Woosung passenger service

Things didn’t get any easier for the men from Ipswich after the railroad was completed. Not long after the line was put into service a depressed Chinese man laid down on the tracks and was decapitated by a train leading to a diplomatic incident.

Perhaps the biggest problem was that the Woosung Road Company, who had initially made a deal with the Chinese authorities for the project, and who had engaged Rapier to carry it out, had bent the truth (to put it mildly), when making the deal. It was no coincidence they had left the word ‘rail’ out of their company name. The authorities were outraged to discover that a railroad was being constructed by Englishmen from Shanghai to Woosung rather than the road they had agreed to.

The original agreement had made provision for the Chinese to buy back the road if they wished; in October 1877 enough cash was raised and the authorities acquired the line. It was thought that with the considerable popularity the line had found with Chinese passengers the service might continue, but this was not to be. On the day the Chinese bought back the line they announced its immediate closure as of 7pm.

The line was torn up and thrown into the river along with the rolling stock and equipment. Less than two years after work commenced on the line it was made to look as if it had never existed. The remaining English workmen, Banks and Jackson, returned to England.

Neither man decided to return to the Ipswich Waterside Works, probably for fear of being sent back to China or somewhere even more remote. Banks went to the Marine Workshop at Parkeston Quay and Jackson became locomotive superintendent on Southwold Railway.

Today this Ipswich venture is close to being forgotten. In China it is often thought that the Kaiping Tramway, built in 1879, was the first Chinese railway and for many British people this is just another example of imperial unwanted interference around the globe that most people would prefer to forget. Good or bad this is still part of our history and quite an expectional part at that. At the very least, these men from Ipswich deserve our respect for their efforts in the face of such trouble.