In the twelfth century Ipswich had a motte-and-bailey and sometime after its capture, in 1153 by King Stephen, it was demolished. These two statements are essentially the only things we know for sure about the town’s missing castle.

In my experience, today, people are usually surprised to learn that Ipswich ever had a castle – as was I. So it seems they would have been in 1735, when the prominent cartographer John Kirby said of the missing castle, it was ‘so entirely demolished that not the least rubbish of it is to be found’.

Facts from the past can be very hard things to hang on to. This was especially the case before the advent of (relatively speaking), new technologies like radio and television, which usefully preserve information from the important to the trivial, from a global to local level. When you also minus the printing press from the equation, or even parish records (which did not become widespread in Europe until the 1500s), even facts like the vague whereabouts of one of the largest manmade structures in a medieval town become fairly transient.

When the Normans invaded England and gained power in 1066 they brought with them the motte-and-bailey castle. The phrase itself came over with them – motte meaning ‘mound’ and bailey meaning ‘enclosure’. The motte was a steep hill with a keep at the top and often a ditch dug out at the bottom. The bailey was an extra layer of defence at the bottom of the motte, which also served as a place to house the followers of the lord who ran the castle. This usually included stables, storehouses, bakeries and houses. Over the next century or so the Normans proceeded to do their best to fill the country with these fortifications; an estimated 1000 were built in England. Historians, such as Robert Malster, are fairly certain that it was this kind of fortification that was built in early 12th century Ipswich.

Artist’s impression of a Suffolk motte-and-bailey castle.

Of course, when you begin to think about it, place names in Ipswich are littered with references to a now forgotten castle of some kind. We have a street, a primary school and an entire voting district (Castle Hill Ward) named after one, to begin with.

So what happened to this structure? Where was it? And are there any recognisable traces of it still surviving in the town today?

There are two theories as to what happened to the castle. John Kirby in The Suffolk Traveller states that the castle was torn down in 1176 on the orders of Henry II, but there is no evidence to support this and nothing to suggest how or why Kirby came to this conclusion. The more likely scenario is that it was destroyed soon after its capture by King Stephen in 1153, for tactical reasons in the war he was then fighting.

The location of the castle is something that has puzzled local historians for quite some time. A few places have been suggested over the years, (mostly outside the centre of the town), but none of them fulfilled the main requirements of a Norman fortification, as Malster puts it: ‘to control the river crossing and the main entrance to the town, and to establish the owner’s authority over the townsfolk’. This was until Keith Wade, a County Archaeologist, stepped up to the plate and suggested a site that does satisfy these criteria.

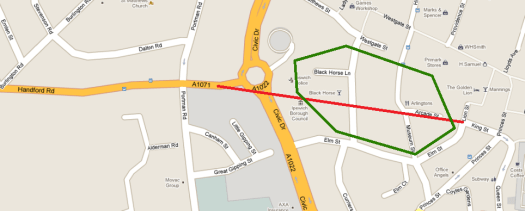

Wade’s clever idea was to look back at the Saxon lay out of the town’s streets, which it turned out were set on a grid pattern, with the roads aligned roughly North-South and East-West. However, Elm Street did not fit into this pattern, it is diverted south to then curve round past St Mary Elms Church. Wade believes that it once ran directly West to link up with Handford road and that the only suitable explanation for this diversion was the earthworks of a motte-and-bailey castle. Another piece of evidence in support of this site is a name, The Mount, used up until the middle of the 20th century for this area, where the Police Station in modern-day Ipswich now stands.

The red line shows where Keith Wade suggests Elm Street use to run before being re-routed by the castle in the 12th century. The green polygon is a suggested site for the, now missing, castle.

As for there being any remaining traces of the castle today – well, no there isn’t, not exactly. If the site explained here was indeed where the castle stood, then we could at least say that the area has been artificially raised and is left over from the earthworks of the castle, but until further evidence comes along to support that, it’s far from being proved.

The most interesting point to be brought out of all this is just how much and how quickly the landscape in England has changed over the past 1000 years. In fact, Ipswich shouldn’t be too put out about misplacing its castle. Of all the castles built by the Normans in the 12th century to defend the new land they had conquered (roughly 1000), only two still survive in any kind of recognisable form today – one in Lewes and one in Lincoln.